The personal accounts of former slaves were incredibly important in strengthening the case for abolition, as they brought to light the harsh realities of the system of transatlantic enslavement. They not only reflect, on an individual and personalised level, general patterns of the transatlantic slave trade and slavery, but also bring into relief and humanise the experiences of the vast majority of individuals whose lives were never recorded and are only seen as statistics.

These accounts were usually (but not exclusively) tales of both struggle and progress or related a spiritual journey, and were either written by the individuals themselves, with or without help, or were told to someone else and transcribed. Their purpose was to arouse the sympathy of their readers and inspire them to campaign against enslavement, as well as to give a voice to the enslaved.

Mary Prince

In her narrative The History of Mary Prince, a West Indian slave, related by herself, published in 1831, Mary Prince writes, ‘I have been a slave, I have felt what a slave feels and I know what a slave knows … hear from a slave what a slave has felt and suffered.’

Mary Prince’s account of her life gives us an insight into the life of an enslaved woman in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Hers is the only known biography of an enslaved woman from the British West Indies, and is more than just a personal story. It was also a contribution to the anti-slavery campaign written by a Black woman who represented those enslaved people whose stories would never be heard.

Born in Bermuda in 1788, Mary’s life was at first relatively tranquil. Purchased and made ‘the pet’ of Betsey Williams, the daughter of her owners, she experienced kindness and affection. However, when Betsey’s mother died in 1798 and her father decided to marry again, Mr Williams sold Mary and two of her sisters to raise money for the wedding. Mary’s description of being sold is told with great sadness:

The black morning at length came; it came too soon for my poor mother and us. Whilst she was putting on us the new osnaburgs [a coarse cloth used for work clothes] in which we were to be sold, she said, in a sorrowful voice (I shall never forget it!), ‘See, I am shrouding my poor children; what a task for a mother!’ … the [other] slaves could say nothing to comfort us; they could only weep and lament with us. When I left my dear little brothers and the house in which I had been brought up, I thought my heart would burst.

Thus, at an early age, Mary experienced loss and separation and came to understand that her life was not her own but subject to the whims of those who owned her.

Her time with Captain Ingham and his wife, her new owners, introduced her to deprivation and hardship. She was witness to the torture of children and the murder of another servant called Hetty, and had first-hand experience of the types of instruments used for flogging: ‘To strip me naked – to hang me up by the wrists and lay my flesh open with the cow skin, was an ordinary punishment for even a slight offence.’

On one occasion she was tied to a ladder and given 100 lashes for accidentally breaking an already cracked vase. On another, she was struck in the back for allowing a cow to wander off – a blow that resulted in a lifelong injury.

Mary Prince’s narrative shows that enslaved workers had to be resourceful and sought the means of survival through a variety of different roles. Women bore many burdens during slavery: in addition to coerced labour and punishment, they had to take care of their owners’ children as well as their own and were often subject to acts of physical and sexual violence.

Like free people, enslaved workers would try to earn money by participating in the economy, combining their work as field hands, domestics and artisans with their own commercial activities. Mary Prince earned money by washing other people’s clothes and selling yams, meat and coffee, with the aim of somehow purchasing her freedom. She persisted towards this end, even though her owners would not allow her to become free.

In her own active way, Mary resisted her enslavement by trying to change her status. For example, unusually she had five owners when most enslaved workers had only one or two during their lifetime. It may have been that she was sold so many times because she was particularly resistance to enslavement. She would demonstrate this by working slowly or feigning ignorance or sickness.

She was very strong willed, and there are instances in her narrative where she is seen to stand up to her owners for their cruel treatment. For instance, without permission, she married Daniel James in 1826, a free Black man who was a carpenter, whom she had met at Moravian church meetings. Mr and Mrs Wood, her owners at this time, were so angry that Mary was flogged with a horse whip. ‘I thought it very hard to be whipped at my time of life for getting a husband – I told her so,’ she later wrote.

When the Woods travelled to London in 1828, taking Mary with them, she finally found a means to escape, although it meant never seeing her husband again.

Mary Prince’s narrative offers a sense of how one woman could overcome psychological and physical trauma and hardship. She highlights not only the horrors of slavery, but also how the human spirit can prevail.

Ottobah Cugoano

In the first personal account of enslavement written by an African – Thoughts and sentiments on the evil and wicked traffic of the slavery and of the commerce of the human species (1787) – Ottobah Cugoano provides a detailed description of being kidnapped as a child off the coast of present-day Ghana:

‘I was early snatched away from my native country, with about 18 or 20 more boys and girls, as we were playing in a field.’

He was then marched to the coast (where he saw Europeans for the first time) to a fort in which he was imprisoned.

He was the first to write What he writes about what transpired when the prisoners were taken from their confinement is second only to Equiano’s account in the amount of detail. Arriving at the coast, Cugoano saw:

many of my miserable countrymen chained two and two, some hand-cuffed, and some with their hands tied behind … I was soon conducted to a prison, for three days, where I heard the groans and cries of many … When a vessel arrived to conduct us away to the ship, it was a most horrible scene; there was nothing to be heard but the rattling of chains, smacking of whips, and the groans and cries of our fellow-men. Some would not stir from the ground, when they were lashed and beat in the most horrible manner … When we were put into the ship, we saw several black merchants coming on board, but we were all drove into our holes and not suffered to speak to any of them. In this situation we continued several days in sight of our native land.

Cugoano also mentions in his narrative a thwarted plot to take control of the slave ship, which was conceived aboard the ship before it got under way:

a plan was concerted amongst us, that we might burn and blow up the ship, and to perish all together in the flames; but we were betrayed by one of our own countrywomen, who slept with some of the head men of the ship, for it was common for the dirty filthy sailors to take the African women and lie upon their bodies; but the men were chained and pent up in holes. It was the women and boys which were to burn the ship, with the approbation and groans of the rest; though that was prevented, the discovery was likewise a cruel and bloody scene.

Upon arrival in the Caribbean he was sold in Grenada where he worked until purchased by an English merchant. He was later taken to England in 1772 where he obtained his freedom and was baptised ‘John Stuart’ at St James’s Church, Piccadilly on 20 August 1773.

Cugoano was servant to Richard Cosway, painter to the Prince of Wales, in London, where he later emerged as one of the leaders of London’s African community. In 1786 he advocated for the rights of a fellow African man by the name of Henry Demane. Demane had been kidnapped and was going to be shipped to the West Indies as a slave. Cugoano enlisted the help of abolitionist, Granville Sharp to take up the case on Demane’s behalf.

Cugoano continued the struggle against slavery with public letters to London newspapers and the publishing of another book, Narrative of the Enslavement of a Native of Africa. He was the first African to demand publicly the total abolition of the slave trade and the freeing of all slaves.

‘If any man should buy another man, and compel him to his service and slavery without any agreement of that man to serve him, the enslaver is a robber and a defrauder of that man every day. Wherefore it is as much the duty of a man who is robbed in that manner to get out of the hands of his enslaver, as it is for any hones community of men to get out of the hands of rogues and villains.’

The book went through at least three printings in 1787, and was translated into French. Copies were sent to King George III, the Prince of Wales, Edmund Burke and other leading politicians in the hopes of changing their views on slavery and the slave trade; all, however, remained supporters of the trade.

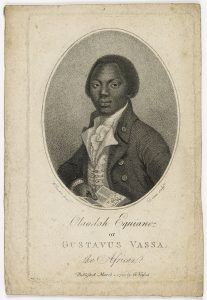

Olaudah Equiano

In The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano (1789), Equiano gives a very detailed account of the violence meted out to the enslaved in Barbados and Montserrat. ‘I was often witness to cruelties of every kind,’ he wrote,

which were exercised on my unhappy fellow slaves … in Montserrat I have seen a Negro man staked to the ground, and cut most shockingly, and then his ears cut off bit by bit … another Negro man was half hanged and then burnt for attempting to poison a cruel overseer.

He notes that, in Barbados, the life expectancy for the enslaved was short: ‘Barbados … requires 1,000 Negroes annually to keep up the original stock, which is only 80,000, so that the whole term of a Negro’s life may be said to be there but 16 years!’

Equiano moved around quite a bit and was bought and sold a number of times in his early life. After Barbados he was taken to Virginia.

There, he was sold to a Royal Navy officer, Lieutenant Michael Pascal, who renamed him ‘Gustavus Vassa’ after the 16th-century Swedish king. Equiano’ name was changed (for the third time) to Gustavas Vassa and he was enlisted in the Royal Navy during the Seven Years’ War (known in North America as the French and Indian Wars). He travelled the oceans with Pascal for eight years, during which time he was baptised and learned to read and write. Equiano was a skilled and experience sailor but he never worked on a plantation. By the time he was an adult, he was too well educated and highly skilled, therefore too valuable to be sent into the fields. Pascal went back on his promise to free Equiano after the war and sold him instead at the end of 1762.

Pascal had sold Equiano to a ship captain from London, who took him to Montserrat, where he was sold again to the prominent merchant Robert King. King, trained him as a ‘gauger’ – a kind of 18th-century quality control manager who ‘gauged’ weights and measures – to work on ships.

Though escaping the harsh conditions of the plantation, Equiano witnessed such brutality in Montserrat he became determined to acquire his freedom at all costs. Equiano also worked as a deckhand, valet and barber for King aboard ship and earned money by trading on the side. In a few years Equiano had earned enough to buy his own freedom. After which, he spent the next 20 years travelling around the world.

In 1786, Equiano went to London and became involved in the abolitionist movement. He was a prominent member of the ‘Sons of Africa’, a group of African men who campaigned for abolition.

Then in 1789 he published his autobiography, ‘The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano or Gustavus Vassa, the African’. His narrative became popular with many prominent subscribers. In the book, Equiano described his experiences during the Atlantic crossing in his writings, which became one of only a handful of published accounts that recount life in West Africa prior to enslavement.

Equiano travelled extensively to promote his book and the abolitionist cause. In 1792, he married an Englishwoman, Susanna Cullen, and they had two daughters – Anna Maria and Joanna. Equiano died on 31 March, 1797, before seeing the end of transatlantic enslavement in the British colonies in 1838.

James Albert Ukawsaw Gronniosaw

In 1770, James Albert Ukawsaw Gronniosaw (1705–1775), wrote the first slave narrative by an African – A Narrative of the Most Remarkable Particulars in the Life of James Albert Gronniosaw, an African Prince, as Related by Himself . In it, Gronniosaw, a Muslim from Bournou in what is now northern Nigeria, describes in great detail how, at around the age of 15, his parents voluntarily let him accompany a merchant from the distant Gold Coast and how he was ultimately sold there as a slave to a Dutch trader.

Gronniosaw was born in Bournou as the youngest of six children. His mother, was the eldest daughter of the reigning King of Zoara.

In around 1725, he was shipped on a Dutch slave vessel bound for Barbados, where he was sold to a Calvinist minister who took him to New York. There he worked as a domestic: ‘He dress’d me in his livery, & was very good to me. My chief business was to wait at table, and tea, & clean knives, & I had a very easy place.’

Gronniosaw later enlisted as a cook on a privateer ship and then as a solder in the British Army. He served in Cuba and Martinique, and eventually settled in England.

His narrative has some similarity with Equiano’s in that, although they both experienced enslavement, they did not remain slaves. Their circumstances were unusual in that they became associated with people who were not solely involved in the slave trade. Equiano was sold to a navy captain, and so he too was in the navy, where he learned to read and write in English, which changed his status. Gronniosaw served in the British army.

After moving to England Gronniosaw first landed in Portsmouth and the London where he met and married a poor English widow. They and their children fell on unfortunate circumstances and moved numerous times to support themselves. Gronniosaw’s account, written with a view to improving his financial situation, was published when there was a growing opposition to Britain’s involvement in transatlantic enslavement.

Not much is known about his life after publication, however a local historian in Chester, discovered a short obituary in the The Chester Chronicle, dated 2 October 1775:

‘On Thursday died, in this city, aged 70, James Albert Ukawsaw Gronniosaw, an African prince, of Zoara. He left the country in the early part of his life, with a view to acquire proper notions of the Divine Being, and of the worship due to Him. He met with many trials and embarrassments, was much afflicted and persecuted. His last moments exhibited that cheerful serenity which, at such a time, is the certain effect of a thorough conviction of the great truths of Christianity. He published a narrative of his life. Chester St Oswald’s Burial 28th Sept. 1775.