People from the ‘Gold Coast’ (modern-day Ghana) – Akan, Ashanti and Coromanti – were often at the forefront of slave revolts in Jamaica during the 17th and 18th centuries. About 300 of them revolted in the parish of St Ann in 1673. In the parish of Clarendon 17 years later, 400 Coromanti burned down Sutton’s estate and fled to the hills. In 1745, Akan-born slaves revolted in the south-eastern parish of St Thomas.

The rebellion begins

The most important slave revolts in Jamaica’s history occurred in 1760 following 20 years of relative peace under treaties between the British and the maroons. They first broke out on Tuesday, 8 April at a plantation in the northern parish of St Mary. These first rebels were believed to comprise upwards of one hundred Africans from the Gold Coast, newly imported, and their leader was a Coromanti man (of the Akan people) known as Tacky.

The speed of the initial assault enabled the rebels to overpower British forces at Fort Haldane at Port Maria where they obtained arms and ammunition. They moved on to overrun the plantations at Heywood’s Hall and Esher. By dawn the following morning, hundreds strong, they had fought their way inland, capturing estates and killing European settlers where they found them.

The maroons assist the British

When, two days later, the lieutenant governor of Jamaica received news of the destruction, he dispatched a detachment from the 74th West India Regiment and another from the 49th, together with three companies of maroons from Nanny Town, Crawford Town and Scotts Hall.

Under the terms of their peace treaty, the maroons were obliged to assist the British in the suppression of uprisings and the recapture of runaways. In addition to rewards for every rebel killed or captured, they were also paid 7 pence and 1 half-penny per day. Their officers received 2 shillings and 6 pence.

Tracked down and killed

Tacky’s campaign spurred on uprisings on estates in the parishes of Westmoreland, St John, St Thomas in the East, Clarendon and St Dorothy’s. These revolts would not be quelled for several months.

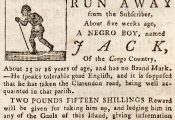

Meanwhile, Tacky’s forces took to the mountains where they were joined by a group of runaways who had previously been enslaved on the French island of Guadeloupe. These men had been involved in an armed uprising there and so had ‘seen something of military operations in which they acquired much skill’. But despite a number of strategic victories, the rebels were eventually tracked down and killed by parties of maroons – Tacky was reportedly shot by one of their sharpshooters.

In all, some 400 rebels were executed and about 600 were sent to be enslaved workers in the Bay of Honduras for their parts in the revolt. The suppression of the uprisings cost an estimated £15,000, and the loss of property stood at £100,000.

As a result of Tacky’s Rebellion, the lieutenant governor petitioned the king to increase the number of regular troops in Jamaica as ‘the forces in this island … were with great difficulty capable of reducing the rebellions’. It was further proposed that, given their leading role in revolts, a Bill should be passed to impose prohibitions on the number of enslaved Coromanti people entering Jamaica. However, the great demand for able labour from the Gold Coast meant that no such legislation was ever enacted.