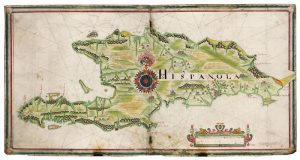

The island of Hispaniola, which is today shared by the Dominican Republic to the east and Haiti to the west, was the first permanent European settlement in the Americas.

The island of Hispaniola, which is today shared by the Dominican Republic to the east and Haiti to the west, was the first permanent European settlement in the Americas.

Sugar and slaves

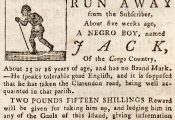

Sixty years after Christopher Columbus’s arrival there in 1492, the indigenous population had been reduced from 600,000 to 500 due to harsh treatment and European diseases. The demand for labour led to the introduction of enslaved Africans to work the island’s mines and plantations. By the end of the 18th century, St Domingue was a French colony, occupying the western half of the island and accounting for two thirds of France’s overseas trade. Sugar was the most important crop. In excess of 450,000 enslaved Africans working on the colony’s 800 plantations produced more sugar than all the islands in the British Caribbean combined.

The remaining 70,000 people in St Domingue were either grand blancs (European planters and aristocrats), petits blancs (skilled and unskilled European workers and tradesmen) or gens de couleur (of mixed African/European background). While the gens de couleur controlled one third of St Domingue’s wealth (mainly through inherited plantations), they were prohibited from voting, holding positions in government, residing permanently in France or even sitting beside a European person in church.

All parties on the island had reason to be wary and resentful of each other.

The revolution begins

In 1789, the French Revolution, with its promise of individual liberty, freedom of expression and equality before the law, was the spark that would lead to the only successful slave revolt in history: the Haitian Revolution. By 1804, Haiti would become the first independent Black Republic in the world.

The first challenge to the status quo came from a revolt of the gens de couleur in 1790 after the colony’s Assembly refused to sanction their right to vote, even though this had been granted by the National Assembly in Paris. But on 14 August 1791, this struggle rapidly faded into the background, when a coordinated mass slave rebellion broke out.

It was supposedly initiated during a traditional African religious ceremony in the Bois Caiman presided over by Boukman, a spiritual leader. The following morning, the whole district was under the control of the rebels, and by 30 September, around 800 coffee plantations and 200 sugar estates had been destroyed and 1,000 Europeans killed.

Toussaint L’Ouverture

Following the execution of the French king Louis XVI in Paris in January 1793, the course of the Haitian Revolution was marked by the rise of the slave general Toussaint L’Ouverture. Amongst other rebel fighters, Toussaint started out with a few hundred men fighting alongside fellow slaves in the struggle for freedom. With military prowess and strategic fighting ability, he and his men became a well-known force to be reckoned with. It is believed that French commanders gave him the name, L’Ouverture (meaning the opening) based on his ability to create ‘an opening everywhere.’

Following a breakdown in negotiations with the colonial Assembly, Toussaint came to believe that military action was the only route to freedom. Over the next four years, he led his forces against a swirl of constantly changing alliances, not only with republican France and the gens de couleur, but also with the Spanish and the British (both of whom sought to use the conflict for their own ends).

By 1795, Toussaint had managed to expel both the British and Spanish forces. He then marched east to take over the Spanish portion of the island where he proceeded to abolish slavery.(Those this part of the island would later be reclaimed by the Spanish) As master of Haiti, he moved to get the plantations back at the centre of the economy and signed trade agreements with Britain and the United States. He offered protection to returning planters who vowed to accept that their workforce would now expect payment for their labour. Finally, he pledged loyalty to France.

Betrayal and independence

In 1799, France’s new ruler, Napoleon Bonaparte, vowed to restore France’s Caribbean empire and sent an expedition of 20,000 men to the island under the command of his brother-in-law General Victor-Emmanuel Leclerc. Toussaint came to terms with Leclerc in May 1802 under an agreement that slavery would not be reintroduced and that he would be allowed to keep his army. However, during the negotiations, Toussaint was deceived, captured and transported to France where he died in prison in April 1803.

This act of betrayal prompted two of his generals, Henri Christophe and Jean-Jacques Dessalines, to wage merciless war against the French, whom they eventually expelled from the island. Haiti was declared an independent nation on 1 January 1804.

The Haitian constitution of the following year granted citizenship to all former slaves and conferred automatic citizenship on any Black person who arrived in the country.

After Independence

Following Haiti’s independence, former French slave-owners made a claim to the French government, for monies lost as a result of the enslaved Africans liberty in independence. In 1825, the French King, Charles X, demanded that Haiti pay an “independence debt” to compensate former colonists for the loss of profits since the former slaves had won their freedom in the Haitian Revolution.

With the threat of prolonged battle looming, (12 French warships with 150 cannons). Haiti had no choice but to agree to pay its former coloniser 150m gold francs – ten times the nation’s total annual revenue. Haiti was also forced to finance the debt through loans from a single French bank, which capitalised on its monopoly by with exorbitant interest rates and fees; a trade blockade was also imposed to limit Haiti’s ability to trade with other nations. The original sum of the compensation was later reduced, but Haiti still disbursed 90m gold francs to France. This second price the French demanded for the independence Haitians had won in battle was, unlawful even in 1825. When the original sum was imposed by the French King, the slave trade was abolished. Therefore, such a transaction – exchanging cash for human lives valued as slave labour – represented a gross violation of both French and international laws. And Haiti did not finish paying off this “independence debt” until 1947 – 140 years after the abolition of the slave trade and 85 years after the emancipation proclamation.

The cost of this debt to a newly established economy would impact the growth and infrastructure of the country for centuries to come. A raft of corrupt leadership and extreme poverty rendered Haiti one of the poorest nations in the western hemisphere. This became most evident when a catastrophic magnitude 7.0 Mw earthquake struck the country on 12 January 2010. The quake killed over 300,000 people and injuring nearly the same amount, and leaving over 1 million people homeless. Since then there have been international calls for France to repay Haiti’s ‘independence debt’, whilst other nations have forgiven all outstanding debt in an effort to help the country to recover from the earthquake’s devastating effects.