Until recently, many commentators on Africa claimed that African societies had no tradition of writing. With the rediscovery of ancient manuscript collections, some dating back to the 8th century AD, this perception is changing.

Until recently, many commentators on Africa claimed that African societies had no tradition of writing. With the rediscovery of ancient manuscript collections, some dating back to the 8th century AD, this perception is changing.

Approximately 250,000 old manuscripts still survive in modern Ethiopia. Thousands of documents from the medieval Sudanese empire of Makuria, written in eight different languages were unearthed at the southern Egyptian site of Qasr Ibrim. Thousands of old manuscripts have survived in the West African cities of Chinguetti, Walata, Oudane, Kano and Agadez.

Despite the many dangers posed by fire, floods, insects and pillaging, some one million manuscripts have survived from the northern fringes of Guinea and Ghana to the shores of the Mediterranean. National Geographic estimates that 700,000 manuscripts have survived in Timbuktu alone.

The Timbuktu manuscripts

Around 60 libraries in Timbuktu are still owned by local families and institutions, collections that have survived political turbulence throughout the region, as well as the ravages of nature. A good example is the Ahmed Baba Institute, established in 1970, which was named after the famous 16th/17th-century scholar, the greatest in Africa.

Ahmed Baba wrote 70 works in Arabic, many on jurisprudence but some on grammar and syntax. Deported to Morocco after the Moroccan invasion of Songhay in 1591, he is said to have complained to the sultan there that the latter’s troops had stolen 1,600 books from him and that this was the smallest library compared to those of any of his friends.

Today, the Ahmed Baba Institute has nearly 30,000 manuscripts, which are being studied, catalogued and preserved. However, during the period of French colonial domination of Timbuktu (1894–1959), many manuscripts were seized and burned by the colonialists, and as a result, many families there still refuse access to researchers for fear of a new era of pillaging. Other manuscripts were lost due to adverse climatic conditions – for example, following droughts, many people buried their manuscripts and fled.

The manuscripts themselves range from tiny fragments to treatises of hundreds of pages.

Four basic types have survived:

- key texts of Islam, including Korans, collections of Hadiths (actions or sayings of the Prophet), Sufi texts and devotional texts

- works of the Maliki school of Islamic law

- texts representative of the ‘Islamic sciences’, including grammar, mathematics and astronomy

- original works from the region, including contracts, commentaries, historical chronicles, poetry, and marginal notes and jottings, which have proved to be a surprisingly fertile source of historical data.

The manuscripts themselves are of special importance to their owners for a number of reasons. For example, many people who are descended from the servile classes but claimed noble descent have been caught out by evidence from the manuscripts. Other manuscripts have revealed the unjust dealings of one family with another that may have happened a long time ago but have a bearing on today, such as in disputed land and property ownership.

It begs the question as to why the worth of these manuscripts been recognised before now. During the colonial period, many of the owners hid their manuscripts or buried them. In addition, French was imposed as the main language of the region, which meant that many owners lost the ability to read and interpret their manuscripts in the languages in which they had originally been written. Finally, it is only wince 1985 that the intellectual life of this region has been revived.

Origins and evolution of Timbuktu

According to the 17th-century historian Abdurrahman As-Sadi, the history of the West African desert region could be divided into the rise and fall of three great empires – ancient Ghana, medieval Mali and the Songhay empire.

Ancient Ghana

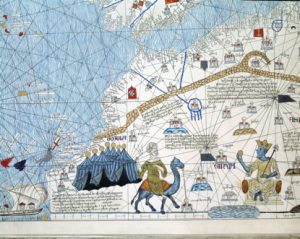

The oldest of the three empires, ancient Ghana at its height ruled territory comprising what we would now call Ghana, Senegal, Gambia, Mauritania, Guinea and Mali, located between two great rivers: the Senegal and the Niger. Timbuktu was founded during the dominance of the Ghana empire, in around AD 1100, by Sanhaja desert nomads, who had a tradition of camping near the Niger in the dry season and taking their animals inland to graze during the rainy season.

There are several explanations for the origin of the name of the famous city. One account suggests that, while the nomads were away, their belongings were entrusted to their slaves, one of whom was called Buktu. The campsite thus became known as ‘Tim Buktu’, meaning ‘well of Buktu’. What began as a semi-permanent nomadic settlement evolved into town and, ultimately, into a city that, between 1100 and 1300, was a thriving economic centre.

Located at a hub of commercial exchange between Saharan Africa, tropical Africa and Mediterranean Africa, Timbuktu was a magnet that attracted both men of learning and men of commerce. It benefited from the gold trade coming from the southern reaches of West Africa – in the 14th century, approximately two thirds of the world’s gold came from West Africa – as well as from the salt trade arriving via the Sahara.

The products that reached Timbuktu included textiles, tea and, later, tobacco. Judging from the number of poems about tea found among the manuscripts of Timbuktu, this was clearly a special commodity. Timbuktu scholar Ahmed Baba gave his approval to tobacco in his On the Lawfulness of Tobacco Usage, in which he claimed that it was neither a narcotic nor an intoxicant!

However, the most profitable trade items in Timbuktu were books. Buying them was considered a socially acceptable way of displaying wealth and a great source of prestige. For instance, an old Timbuktu chronicle Tarikh al Fettash reveals that the king bought a great dictionary for the equivalent price of two horses.

Medieval Mali

As the empire of Ghana declined, the Mali empire took its place, founded by the Mandinka-speaking people ruling from their capital Niani (in what is now Guinea). King Sundiata Keita of Mali conquered ancient Ghana in AD 1240, and two generations later, Mansa Musa I turned the Mali kingdom into an empire. Islam became the dominant religion of the Malian cities and Arabic became the language of scholarship.

Described as the ‘Latin of Africa’, Arabic was useful for communicating between peoples such as the Bambara, Fulani, Hausa, Mossi, Songhay and Tuareg who all spoke different languages. Just as Latin in medieval Europe was associated with Christianity, Arabic in medieval Africa was associated with Islam, and just as Europeans adopted the Latin script to write their own languages, Africans used the Arabic script to write theirs.

In 1999, the BBC broadcast the documentary series Millennium: One Thousand Years of History. The programme on the 14th century opened with the following disclosure: ‘In the 14th century, the century of the scythe, natural disasters threaten civilisations with extinction. The Black Death kills more people in Europe, Asia and North Africa than any catastrophe has before. Civilisations which avoid the plague thrive. In West Africa, the empire of Mali becomes the richest in the world.’

There are a variety of ways in which the empire spent its wealth. The Sankoré University mosque was built in about AD 1300 with funding from a woman of the Aghlal, a religious Tuareg ethnic group. The Sankoré Quarter in north-east Timbuktu became the dwelling place of the scholars and teachers. It was also where the first libraries were created. Scholars and kings acquired books during their travels. They were also bought from merchants coming from the north. Mansa Musa I purchased works on Maliki law. He also ordered the construction of the Great Mosque of Timbuktu in 1326.

There were a number of challenges to Malian hegemony. One came in 1343, when the Mossi attacked Timbuktu. A source says: ‘The Mossi sultan entered Timbuktu and sacked and burned it, killing many persons and looting it before returning to his land.’ Timbuktu, however, recovered and the Malians continued to rule it for the next hundred years. However: ‘The Tuaregs began to raid and cause havoc on all sides. The Malians, bewildered by their many depredations, refused to make a stand against them.’ Mali lost control of Timbuktu in 1433.

The Songhay empire

Once a tributary to the Mali empire, the Songhay became independent as Mali declined. Sonni Ali Ber was their first great king, conquering most of what became the Songhai empire and seizing Timbuktu in 1468. The chronicles say he ‘perpetuated terrible wickedness in the city, putting it to flame, sacking it and killing large numbers of people’. The gold traders there, fearing that Sonni Ali would take control of their goods and transactions, started businesses in the city state of Kano in what is now northern Nigeria. The scholars of Timbuktu were also treated harshly and many fled.

Subsequent rulers of the Askiya dynasty adopted a gentler approach towards the scholars, offering them cash and privileges, especially during Ramadan. These included slaves, grants of land, and exemption from taxation. Major Felix Dubois, the 19th-century French author of the excellent Timbuctoo the Mysterious, says: ‘To ensure them the tranquillity so necessary to a man of thought and letters, their affairs were managed and their properties cultivated by their slaves.’

Timbuktu benefited under the reign of the Askiya kings. According to the Tarikh al Fettash, a 17th-century history of the region:

One cannot count either the virtues or the qualities of [Askiya Muhammad I], such are his excellent politics, his kindness towards his subjects and his solicitude towards the poor. One cannot find his equal either among those who preceded him, nor those who followed. He had a great affection for the scholars, saints and men of learning.

Timbuktu eventually rose to intellectual dominance in the region. In the early days, Walata – ‘where the holiest and most learned men resided’ – and Djenné had been centres of Islamic scholarship. Djenné had a university that boasted thousands of teachers, and there are reports of surgical operations successfully performed by their medical doctors, such as eye cataract surgery. But by 1500, Timbuktu had surpassed both of these centres. Scholars and students visited it from the entire region, including Saharan and Mediterranean Africa, and there were scholarly connections between Timbuktu and Fez in Morocco. In addition, during pilgrimages, connections were made with fellow scholars in Egypt and Mecca.

According to the Tarikh al Fettash, Timbuktu was described as having:

…no equal among the cities of the blacks … and was known for its solid institutions, political liberties, purity of morals, security of its people and their goods, compassion towards the poor and strangers, as well as courtesy and generosity towards students and scholars.

According to Leo Africanus in A History and Description of Africa (c. 1526):

The people of Timbuktu have a light-hearted nature. It is their habit to wander into town at night between 10pm and 1am, playing instruments and dancing … There you will find many judges, professors and devout men, all handsomely maintained by the king, who holds scholars in much honour. There, too, they sell many handwritten North African books, and more profit is to be made there from the sale of books than from any other branch of trade.

Askiya Daud (r. 1549–82), the fifth ruler of the Askiya dynasty, established public libraries and employed calligraphers to copy books for him, some of which were then given as gifts to scholars. The book-copying industry was well structured and extensive. At the end of each book was stated the title, the author, the date of the manuscript copy and the names of the scribes who copied it. Some books also named the proofreaders and the vocalisers (i.e. scholars who added vowels to Arabic), and often they mentioned for whom the manuscript had been copied, the monies involved, who provided the blank paper, and the dates of the beginning and ending of the copying of each volume. Many copyists wrote 140 lines of text per day, while the proofreaders read 170 lines daily. The proofreader of one particular multi-volume text was paid half a mithqal (1.75–2.5g) of gold per volume while the copyist received one mithqal (3.5–5g).

Religion

Timbuktu was also a religious city. According to a West African proverb: ‘Salt comes from the north, gold from the south and silver from the country of the white men, but the word of God and the treasures of wisdom are only to be found in Timbuktu.’ There is a local legend that the city is guarded by 333 renowned saints as well as numerous lesser ones, and surrounding Timbuktu like a rampart are the chapels where the saints are buried.

According to the Sufis, a saint is a Muslim mystic, usually a scholar, who has achieved such closeness to God as to possess special powers. For example, we read: ‘The very learned and pious sheikh Abou Abdallah had no property, and he bought slaves that he might give them their liberty. His house had no door, everyone entered unannounced, and men came to see him from all parts and at all hours.’

The intellectual life of Timbuktu

The Sankoré University mosque was the main teaching venue since many scholars lived in the Sankoré Quarter. Classes were also taught at the Great Mosque and at the Oratory of Sidi Yahia. Most of the teaching took place in the scholars’ houses where each had his own private library that he could consult when knotty points of scholarship arose. Very often a student would study under six or seven different tutors, each with a different specialism.

At the height of the Songhay empire, Timbuktu had 25,000 students. They would pay the lecturers in money, clothing, cows, poultry, sheep or services, depending on how well-off the student’s family was. Students might also work in the local tailoring industry to pay for their studies. According to the Tarikh al Fettash, Timbuktu had 26 textile factories where each master tailor employed 50 to 100 apprentices. Employment was restricted to students at a certain level of education.

Each teacher was expert in a number of texts. This is not quite the same as being an expert in a particular subject. The traditional teaching method involved the lecturer dictating a text of the students. The students would write their own copies and would read back to that lecturer what they had written. All the students would do the same and, in this way, learn from each other’s mistakes. Once the correct version had been written down, the lecturer would explain the technical intricacies of the text and engage in discussion with the students.

Among the manuscripts, treatises on pedagogy have survived. Some books tell how to learn to read and improve memory, give suggestions on what subjects should be taught and detail the qualities of an ideal educator. An ideal student was:

Modest, courageous, patient and studious; he must listen carefully to his professor and have a solid understanding of his lessons before memorising them. The students must learn to debate among themselves to deepen their understanding of the material. They must always have a great respect and a profound love for their teacher, because these are the conditions for professional success.

<h3>The curriculum

Ahmed Baba studied Arabic grammar and syntax, astronomy, logic, rhetoric and prosody. Textbooks were purchased and copied on a number of subjects, including astronomy, astrology, botany, dogma, geography, Islamic law, literary analysis, mathematics (including calculus and geometry), medicine, mysticism, morphology, music, rhetoric, philosophy, the occult sciences, and geomancy.

The works of the Greek astronomer Ptolemy were basic references for Islamic astronomy. The Greek philosophers Plato and Aristotle were also common. The Greek physician Hippocrates was popular, as well as the Persian medical philosopher-scholar Avicenna.

Academic standards of teaching in Timbuktu

The quality of teaching there was as high as in North Africa and the Middle East, and some scholars say it was even higher. A celebrated professor from Hedjaz is reported to have arrived in Timbuktu with the intention of teaching, but after talking to some of the students and seeing their level of learning, he was humbled and decided to become a student himself.

On graduation. after the students had each received a traditional turban, they had a number of career options. Some lecturers issued licences that authorised their best students to teach particular texts. The ulama or scholars had a variety of roles in Songhay society. Some became judges, others became imams and some became teachers. The rural holy men became parish priests, attending to every part of the lives of their flocks.

Timbuktu books

The documents that have been preserved range from one-page fragments to hundreds of pages – one example cited by John O Hunwick and Alida Jay Boye in their masterly The Hidden Treasures of Timbuktu (2008) is a letter of 482 pages. The Timbuktu manuscripts mainly comprise Korans, Koranic exegesis, collections of Hadiths, writings on Sufism, theology, law and other closely related disciplines. By the 15th century, Timbuktu scholars were producing original works as well as compiling new versions and commentaries on established texts.

There are also commercial documents. These typically begin with the phrase: ‘Let all who read this document know …’ followed by the names of buyer and seller, a detailed description of the product, a declaration of the legal validity of the sale, a confirmation that the purchaser paid the price in full and, finally, the name of the drafter and the date. Legal documents also include a statement of the validity of the contract, confirming that the parties were legally competent, free from restraint and in full possession of their mental faculties, and that the transaction was lawful according to Islamic law. They typically end with the phrase: ‘Praise to God and blessings upon the Prophet.’

The reading and writing of poetry was important in these cultures. Among the Timbuktu documents are verses devoted to the Prophet and to the adoration of a particular woman or man, and poems about tea. Poetry was written when a person died, to be read at their funeral. Even works on grammar and law were rewritten in verse to facilitate ease of learning.

A number of manuscripts were written in Ajami – Arabic script used to write local languages. There are Ajami manuscripts in Songhay, Wolof, Hausa, Fulfulde and Tamasheq. These texts are concerned with botany, diplomatic correspondence, occult sciences, poetry and traditional medicine.

The end of Timbuktu’s golden age

The golden age of Timbuktu came to an end with the collapse of the Songhay empire following the invasion by Morocco, whose sultan Ahmad I al-Mansur had established an alliance with Elizabeth I of England.

The English agreed to provide the Moroccan military with firearms and men skilled in the use of these weapons. This Arab-European army invaded Songhay in 1591 and destroyed it. The invaders confiscated gold and other resources, enslaved the Songhay scholars – including Ahmed Baba, who was deported to Morocco – and attempted to confiscate Timbuktu’s archives.

With the end of the Songhay empire, the two thirds of West Africa that had previously been under a single authority split into smaller and smaller political units, making the region easy prey for invaders and slave traders.

In 1656, the great West African historian Abdurrahman As-Sadi wrote in his Tarikh as Sudan: ‘I saw the ruin and collapse of the science of history. I observed that its gold and small change were both disappearing.’