Once the captured Africans arrived at the Atlantic, they were taken to one of the many slave forts that could be found along the coastline, where they would wait to be transported by ship to the Americas. Held in the most deplorable of conditions, they would languish in these dungeons, sometimes for months, waiting for slave ships to come and collect them. Many died there, and all of them left mentally distressed.

Once the captured Africans arrived at the Atlantic, they were taken to one of the many slave forts that could be found along the coastline, where they would wait to be transported by ship to the Americas. Held in the most deplorable of conditions, they would languish in these dungeons, sometimes for months, waiting for slave ships to come and collect them. Many died there, and all of them left mentally distressed.

These forts, many of which still stand, were built by the politically and economically dominant European nations of the period: Spain, Portugal, the Netherlands, Denmark, France and England.

Heavily fortified against attacks from pirates and from any European nations with which they may have been at war, the forts allowed these slave-trading nations to increase their shipments, develop strong commercial networks in Africa and provide their colonies with a continuous supply of slave labour.

Elmina Castle

Portugal was the first nation to capture and trade in enslaved Africans and quickly developed a commercial network in the region. It sold enslaved Africans in Europe and on the Atlantic islands of Madeira, the Canaries, Cape Verde and the Azores. In 1482, the Portuguese built Fort São Jorge da Mina – now most commonly known as Elmina Castle – to protect their gold trade from their rivals, the Dutch. The first trading post built on the Gulf of Guinea, Elmina made the Portuguese the dominant force on the Gold Coast (present-day Ghana).

Portugal was the first nation to capture and trade in enslaved Africans and quickly developed a commercial network in the region. It sold enslaved Africans in Europe and on the Atlantic islands of Madeira, the Canaries, Cape Verde and the Azores. In 1482, the Portuguese built Fort São Jorge da Mina – now most commonly known as Elmina Castle – to protect their gold trade from their rivals, the Dutch. The first trading post built on the Gulf of Guinea, Elmina made the Portuguese the dominant force on the Gold Coast (present-day Ghana).

The new fort had a considerable effect on Africans living in the region. Elmina declared itself an independent state at the urging of the Portuguese, whose governor then took control of the town’s affairs. The people were offered protection against attacks from neighbouring coastal communities with whom the Portuguese had much less genial relations. If any community attempted to trade with a nation other than Portugal, the Portuguese reacted with aggressive force, often forming alliances with their enemies. Hostilities therefore increased, and the traditional organisation of society suffered, especially following the introduction of guns, which made easier the domination of stronger kingdoms over weaker states.

After years of unsuccessful attempts to acquire the fort the Dutch took possession of Elmina in 1637 maintaining possession until 1871, it was then transferred by treaty to the British.

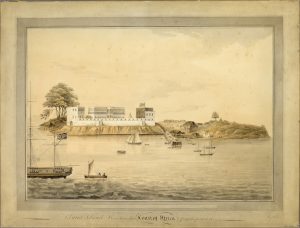

Cape Coast Castle

In 1664, Cape Coast Castle became the headquarters in Africa of the entire English/British involvement in the transatlantic trafficking of Africans. One historian has described it as ‘essentially a defended warehouse within which goods and people could be temporarily stored’.

In 1664, Cape Coast Castle became the headquarters in Africa of the entire English/British involvement in the transatlantic trafficking of Africans. One historian has described it as ‘essentially a defended warehouse within which goods and people could be temporarily stored’.

However, according to one of its governors, it was ‘the grand slave emporium of the British slave trade’. From here enslaved African men, women and children were sold to British slave ships and carried to the Caribbean and North and South America where they were put to work on plantations, in mines, as soldiers or as domestic servants.

The castle itself was like a small city. It had its own postal service, connected to other forts along the coast. Its guns protected ships from armed attack by Britain’s enemies as nations involved in the slave trade were constantly playing out commercial and political rivalries along that coast – and from privateers. There was even a garden where oranges, mangoes, cherries and bananas were grown. The fruit was made into a drink that was sold to slave-ship captains to give to the enslaved Africans and the crew during the Atlantic crossing to reduce the risk of scurvy.

The governor’s quarters was at the very top of the castle, where he was able both to look out to sea and to survey the goings-on of the whole building. These quarters were expensively furnished and included a library.

The ground level was taken up with warehouses containing vast quantities of imported goods such as brandy, tobacco, muskets, knives and gunpowder. There was also a hospital, cook-house and barracks.

Also on this level were the dungeons, with a single entrance. Kept in constant near-darkness, they were known as ‘slave holes’. Anthony How, a botanist who came to this part of the coast in 1785/6 to examine the local plants, was later asked if he had observed how the enslaved were treated. He replied, ‘They were chained day and night, and drove down to the sea twice a day to be washed.’

More than 2,000 miles away were other British forts – in Gambia, in Sierra Leone and, for a time, on Gorée Island in Senegal. With Cape Coast Castle, they were all integrated into a network of ships and shore settlements that formed the African end of the British slave trade.