When the Royal African Company was founded in 1672, it was given a monopoly over the British slave trade. But from the first, it could not satisfy the American planters’ demands for more and more slaves. Nor could it prevent merchants from Bristol and London from encroaching on the trade. Those from Bristol rose to the challenge, and when the monopoly ended in 1698, the city was poised to claim a major share of the slave trading markets of West Africa.

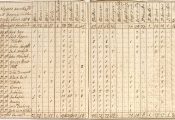

When the Royal African Company was founded in 1672, it was given a monopoly over the British slave trade. But from the first, it could not satisfy the American planters’ demands for more and more slaves. Nor could it prevent merchants from Bristol and London from encroaching on the trade. Those from Bristol rose to the challenge, and when the monopoly ended in 1698, the city was poised to claim a major share of the slave trading markets of West Africa.The British slave trade was then dominated, in turn, by merchants from London Bristol and Liverpool. Until 1725, London led the way, but between 1725 and 1740, Bristol established itself as the major English slaving port. By the 1730s, an average of 39 slave ships left Bristol each year, and between 1739 and 1748, there were 245 slave voyages from Bristol (about 37.6% of the whole British trade). In the last years of the British slave trade, however, Bristol’s share fell to 62 voyages, a mere 3.3% of the trade – compared to Liverpool’s 62% (1,605 voyages).

Spotting commercial potential

Of course, Bristol was a well-established port long before its merchants turned their attention to West Africa. Its location was a great advantage when merchant adventurers began their explorations in the north Atlantic, and along with other western port cities in the 17th and 18th centuries, it benefited greatly from the expansion of transatlantic commerce – of all kinds.

The city’s well-positioned merchants were quick to spot the commercial potential that opened up when the English established their colonies in North America and the West Indies. They were prominent in supplying enslaved Africans to St Kitts (along with Barbados, the pioneering English sugar colony in the Caribbean) and to Virginia (for the tobacco plantations). Indeed, by the mid-17th century, the market in the Virginia tobacco trade had effectively been cornered by merchants from Bristol and London. But by the 1720s, Bristol merchants were shipping twice as many Africans to the Virginia as their London rivals.

They were able to do this because they had forged good trading relations in specific regions of West Africa. Bristol men had important ties, first, in Calabar and then in Bonny (both now part of south-east Nigeria) and in Angola. There, they formed liaisons with local trader dynasties that survived for generations and which were secured by bonds of trust. Such trust was clearly vital in commercial dealings spread over huge distances and over such protracted periods.

Physical fabric

Bristol thrived as a city because of its slave trading success. Its urban development– the growth of its handsome physical fabric, similar in many respects to that of the French cities of Nantes and Bordeaux – was directly linked to the slave trade and to Bristol’s general trade to the slave colonies. Similarly, there were important links between Bristol’s slave trade and the growth of the city’s industries, notably copper-smelting, sugar-refining and glass-making.

Ultimately, however, it was Bristol’s relatively less-developed industrial hinterland and its smaller regional population that were to play a part in the city’s eventual relegation behind Liverpool as the nation’s major slaving port. Slower local industrial and population growth meant that Bristol slipped behind Liverpool from the 1740s onwards.

Thereafter, though still a thriving port city, Bristol was no longer the nation’s premier slaving port. But its involvement in, and benefits from, the slave trade can still be seen in all corners of the city’s surviving 18th-century physical fabric.