The voyage of Christopher Columbus from Spain to the Americas in 1492 opened up that part of the world to European economic activity. He and his men seized the continents of North and South America without any regard for or payment to the Native Americans. The indigenous peoples were themselves enslaved and then died out from diseases by the millions.

Africans were then captured and taken as replacements. The Spanish required labour chiefly for agricultural production and mining – gold and silver were exported in large quantities to Europe from the mines in Mexico, Peru and elsewhere. Eventually, in 1543, the Spanish created the asiento – a contract given to foreigners to supply enslaved Africans to the Spanish colonies.

The involvement of other Europeans

By the end of the 16th century, the Portuguese and Spaniards dominated the trafficking of Africans to their colonies in Central and South America. However, by the beginning of the next century, other European nations were also participating.

The Dutch built Fort Nassau on what would become the New Jersey shore of the United States, and obtained Gorée Island, Elmina Castle and Axim in West Africa. In 1621, the Dutch West India Company was founded to spearhead Dutch involvement in the transatlantic slave trade and the colonisation of Curaçao, St Eustatius and Tobago in the Caribbean and New Amsterdam (now New York) in North America.

The English colonised Barbados, Maryland and Virginia, and in 1618, James I gave a charter of monopoly to 30 London merchants to engage in the enslavement and trafficking of Africans. The French, the Danes and other Europeans also became increasingly involved in the slave trade, and all the European powers fought over and established colonies in the Caribbean and other parts of the Americas.

After about 1640, there was an economic revolution in the Americas as tobacco, coffee, cotton and, most importantly, sugar became the most profitable cash crops cultivated on large plantations. This led to an even greater demand for the labour required to cut and grind cane, transform the output into sugar and make molasses and rum, which in turn resulted in the massive expansion of the slave trade. As the historian Basil’ Davidson has put it, the scale of enslavement exploded from a ‘trickle’ to a ‘flood’. England and France became the dominant powers in this new system of enslavement and exploitation that linked Europe to Africa and the Americas, a system sometimes known as the ‘Triangular Trade’.

How did the “Triangular Trade” work?

Europe to Africa

On the first leg of the triangular trade route voyage a slave ship would set sail from Europe laden with goods for sale to exchange with slave traffickers based in Africa. The most important single product comprised textiles, initially made in India but increasingly in Europe. Other products included horses, guns, cannons, brass, glass, iron bars, tobacco, oils and soaps. At the point of sale on the African coast, the first set of European profits would be made.

In 18th-century France, it was estimated that it cost 250,000 livres to outfit a slave ship, about the same price as a large home in a prestigious Parisian street. The finance was raised by setting up partnerships and joint-stock companies, some protected by royal monopolies.

The slave dungeons in Africa (also called slave ‘castles’ and ‘forts’) were also owned and maintained by European investors, who also paid the managers, brokers, agents and ship captains. However, they were often located on land rented from African rulers. These rulers and other powerful Africans were frequently those who provided African captives, who were mostly taken in civil war, in exchange for manufactured goods from Europe.

Africa to the Americas

On the second leg of the triangular trade route journey from Europe, slave ships would set sail from Africa laden with enslaved people for sale to the slave owners in the Americas. These ships and their captives were insured. Originally, Amsterdam led the way in the insuring of ships and cargoes in the 17th century, to be surpassed by London in the following century. One such English insurer was Lloyds of London.

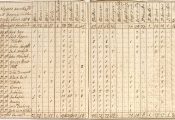

Of particular concern to the enslavers was keeping enough of the captives alive during this second voyage to turn them a profit at its end. They argued over how many enslaved Africans could be packed into a ship, some advocating ‘tight packing’ while others opted for ‘loose packing.’ At the point of sale in the Americas, the second set of profits would be made, assuming that enough captives survived the journey.

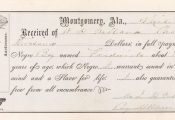

Enslaved people were viewed in at least three ways by the American and Caribbean slaveholders. They were (1) a commodity that could be sold, (2) an object that could be rented and (3) a producer of cash crops (cotton, sugar, tobacco and rice) and other forms of income (mining, construction, even prostitution) for their enslaver.

The Americas to Europe

On the final leg of the triangular trade route voyage, a slave ship would set sail from the Americas laden with minerals, tobacco and foodstuffs, all produced by forced labour, for sale in Europe. At the point of sale, the third set of profits would be made, enhanced because the land on which the enslaved people worked had already been taken from Native Americans without significant payment.

Some of these products became inputs into European industries, and industries developed from this trade. England, for example, accumulated much capital and had enhanced economic development in shipbuilding, seaports and manufacturing centres, banking and insurance, textiles, sugar refineries and metallurgy.

Birmingham became a centre of iron manufacturing, producing guns and shackles for use in mass enslavement. Bristol and Glasgow were centres for curing tobacco and refining raw sugar cane. Other sugar-related industries boomed, such as the production of sugar and molasses pots and rum decanters. Bristol merchants built large Georgian houses in leafy parts of the city.

Liverpool’s rise as a city was also based on mass enslavement, businesses there controlling some 40% of the European trade in the late 18th century. Between 1787 and 1801, all but one of Liverpool’s 20 mayors were connected to enslaving activities in some way.

A big money game

The transatlantic slave trade emerged as one of the most lucrative transnational enterprises ever and fuelled the development of the new economic system of capitalism in Europe. Moreover, some of the wealth and property accumulated then, and many of the institutions created in that era, still exist today.

The slave trade required the skills of advanced management, complex financial arrangements and various complex investment instruments. Resources were pooled through the creation of joint-stock companies and powerful monopolies. It was a big money game that attracted the rich and famous of the major European nations, lured by the possibility of making a quick fortune. The trade also offered some small-time merchants the opportunity to buy their way into the aristocracy.

For example, among the investors of the South Sea Company – a company that, in 1713, bought from the British government the asiento contract to supply 5,000 captives to Spanish colonies – were Thomas Guy (founder of Guy’s Hospital), Sir Isaac Newton, Alexander Pope and Jonathan Swift. The first governor of the company was the chancellor of the Exchequer, while the monarch, Queen Anne, received over 22% of the company’s stock. (In 1720, the company failed spectacularly in what became known as the ‘South Sea Bubble’.)

Finally, the slave traders themselves used the trade to give them a boost into the upper reaches of society. David and Alexander Barclay, enslavers from Jamaica and active in 1756, married into the banking families of Gurney and Freame, ultimately creating Barclays Bank. In 1762, Francis Baring, another slave trader, founded Barings Bank – the same institution that was spectacularly brought down in 1995 by the ‘rogue trader’ Nick Leeson. Thomas Leyland, another slave trader, became a partner in one of Liverpool’s oldest banks in 1802. After a series of takeovers, Leyland Bank which eventually became HSBC.