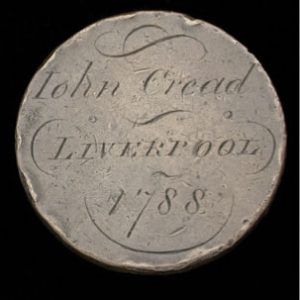

Bristol continued its involvement in the slave trade until abolition but in decreasing numbers in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. By that stage, other commodities were needed, not just copper but manufactured goods – textiles, iron, leather and ceramics – and the northern ports and Liverpool in particular were best able to furnish these.

Bristol continued its involvement in the slave trade until abolition but in decreasing numbers in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. By that stage, other commodities were needed, not just copper but manufactured goods – textiles, iron, leather and ceramics – and the northern ports and Liverpool in particular were best able to furnish these.Cost-cutting

By the 1780s, Liverpool had become the largest slave-ship construction site in Britain, with two out of every five vessels being built there. Liverpool had other advantages. For instance, the payment of duty could be evaded by storing goods on the Isle of Man, 80 miles to the north-west.

The city was also notorious for cost-cutting practices: young boys and inexperienced hands would be employed in preference to able seamen; officers and crew were paid on an annual rather than monthly basis; and agents were permitted only a 5% commission on transactions. Effectively, Bristol was squeezed out of the trade by the bigger, more profitable Liverpool ships that were less costly to operate.

Liverpool merchants also created a successful, though illegal, trade in enslaved Africans to the Spanish empire.

Huge fortunes

The first recorded slave voyage from Liverpool was in 1700: the Liverpool Merchant, which transported 220 African captives to Barbados. Following the success of that venture, the slave trade came to the attention of the city’s elders who threw themselves into it with great abandon. Huge fortunes, which would later become the building blocks of banks and manufacturing interests, had their origins in the Liverpool slave trade.

The Heywood brothers, Arthur and Benjamin, made their fortunes in the slave trade. The bank they founded on their profits – Arthur Heywood & Sons & Co. – would be absorbed in turn by the Bank of Liverpool, Martin’s Bank and Barclay’s Bank.

Another old high street bank with connections to the slave trade can be traced back to the launch of Thomas Leyland’s banking house in 1807. Leyland was one of the three richest men in Liverpool and served as the city’s mayor in 1798, 1814 and 1820. Between 1782 to 1807, he was responsible for the trafficking of almost 3,500 Africans to Jamaica alone. In 1901, Leyland & Bullin’s Bank would become part of the North & South Wales Bank, which in turn would be absorbed into the Midland Bank in 1908.

‘Attorneys, drapers, grocers …’

Several other Liverpool mayors and members of Parliament were also involved in the slave trade. Thomas Johnson, a slaver since 1703, was an MP from 1701 to 1723. His son-in-law Richard Gildart and cousin James Gildart were, between them, mayors of Liverpool on five occasions from 1714 to 1750.

The city expanded spectacularly. As was the case in London, Bristol and elsewhere, small business entrepreneurs of all ranks also invested in the trade in human lives. J Wallace, a Liverpool historian, wrote in 1795:

… almost every order of people is interested in a Guinea cargo. It is well known that many of the small vessels that import about a hundred slaves are fitted out by attorneys, drapers, grocers, tallow-chandlers, barbers, taylors [sic] etc. …