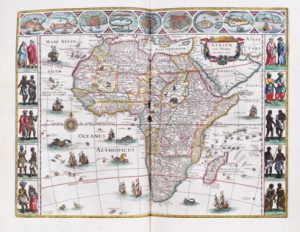

One of the most important legacies of the transatlantic slave trade and also of colonial rule in Africa and the Caribbean has been the creation of the modern African diaspora – the dispersal of millions of people of African origin all over the world but especially in Europe and the Americas.

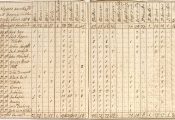

The largest populations of people descended from those who were forcibly transported from Africa are in Brazil, though not precisely listed in census returns, but it may be as high as 90 million – about half of Brazil’s entire population in 2010, in the Caribbean (approximately 40 million), the United States (another 40 million) and many millions more in other countries. This would not be too surprising as more enslaved Africans, (roughly 4 million) were taken to Brazil than to any other country. In addition, slavery lasted longer in Brazil than in other countries, not being finally abolished until 1888.

Pan-Africanism

The legacy of the transatlantic slavery, especially racism and colonialism, has meant that those who are part of the African diaspora have suffered similar problems and disadvantages. This fact contributed to the emergence of Pan-Africanism, a movement and body of ideas that sought to unite all people of African descent, link them to Africa and attempt to organise and protest against racism and colonial rule.

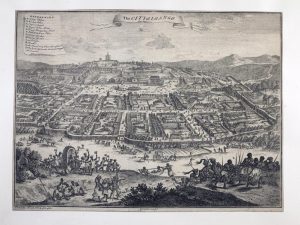

Mainly because Britain had the largest colonial empire, the first Pan-African conference was held in 1900 in London, organised by Trinidadian lawyer Henry Sylvester (1869–1911) of the London-based African Association. Later, the African-American writer and activist W E B Du Bois (1868–1963) organised other Pan-African congresses, which were held in Europe and the United States.

In the early 20th century, however, the most famous advocate of Pan-Africanism was the Jamaican, Marcus Garvey (1887–1940). His Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), with its headquarters in New York, had millions of supporters throughout Africa and the diaspora, inspired by Garvey’s call for racial pride, the notion of ‘race first’ and his famous slogan: ‘Africa for the Africans at home and abroad.’ Other famous Pan-Africanists include the Trinidadian, George Padmore (1903–59), who organised the 1945 Pan-African congress in Manchester in the UK, and Aimé Cesaire (1913–2008), a writer and politician from Martinique, who was one of the founders of the Négritude movement in France in the 1930s.

The impact on global culture

The African diaspora has had a considerable impact on global culture, especially during the 20th century, in the fields of science and medicine, music and popular culture. The most generally recognised contributions to culture came from the United States, where African-American music genres such as jazz, gospel, blues, soul and rap/hip hop transformed and dominated popular music throughout the century.

Reggae, salsa and calypso – types of music that originated in Jamaica, Cuba and Trinidad, respectively – have also had an impact on worldwide popular culture. Alongside music can also be mentioned the influence that the diaspora has had on dance, fashion, language and culture. In these areas, African-American culture has also been particularly significant.

Rastafarianism

Another significant cultural influence has been Rastafarianism, the religious movement that first emerged in the 1930s and takes its name from Ras Tafari (1892–1975), who later became Haile Selassie I, emperor of Ethiopia. This movement was strongly affected by some of the ideas of Marcus Garvey, whom many Rastafarians regard as a prophet.

It came to global prominence during the 1970s because of its strong influence on reggae and, in particular, as a result of the status of Bob Marley, the reggae industry’s superstar and follower of the movement. Its most lasting impact has been the popularity of ‘locks’, a hair style that was at one time associated with the religion. ‘Locking’ ones hair has since become more fashionable and disassociated with the religion, and has gained in popularity across many cultures throughout the world.

The diaspora in Britain

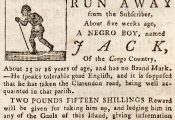

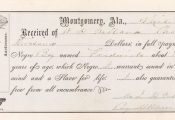

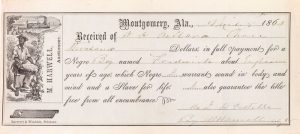

A population of African origin has existed in Britain since at least the 16th century and probably for some time before that: evidence of British residents of African descent can be traced back to Roman times. However, Britain’s participation in the transatlantic slave trade meant that thousands of Africans also came to Britain either as enslaved people or as servants and workers in a variety of occupations.

Africans played an important part in the abolition movement of the 18th century – not only as writers and propagandists such as Equiano and his comrades in the Sons of Africa organisation, but also as participants in debates and other activities throughout the country.

From that time, significant numbers of free African men joined the armed services, and it was therefore common to find those of African descent employed as military musicians as well soldiers and sailors in most of the major battles waged by the British army and navy, including Trafalgar and Waterloo. By the dawn of the 20th century, distinct communities of mainly African and Caribbean men and their families had grown up in many of Britain’s port cities, including London, Cardiff and Liverpool.

The First World War

Soldiers and sailors from the African diaspora played an important role in World War I. Black troops from the colonies were recruited by all the major colonial powers, as well as by the United States and Canada. France, for example, recruited over 230,000 troops from Africa alone, as well as more than 23,000 from the French Antilles. Many Black people resident in Britain at the time joined their local regiments in Britain or the British West Indies Regiment, which recruited over 15,000 Caribbean men during the war. Black seafarers resident in Britain also took part in the war, many losing their lives – over 1,000 from Cardiff alone.

As well as providing soldiers, the British Caribbean contributed food and money to the war effort. However, many of the British West Indies Regiment and the West India Regiments were prevented from frontline fighting on the Western Front because of racist views in the army, although these regiments were actively involved in fighting in Palestine and elsewhere.

It is estimated that over 1,200 Caribbean servicemen lost their lives during the First World War, and many of those who survived received commendations and awards for bravery. The best-known Black soldier to lose his life during the war was Walter Daniel Tull (1888–1918) who had also been a famous footballer.

Tull was also notable because he had been made an officer, an extremely rare occurrence at the time because all the British armed forces operated a colour bar, preventing those not of ‘pure’ European descent from receiving commissions and commanding troops. Racism was a constant problem faced by Caribbean troops and, in 1918, led to a mutiny among soldiers of the British West Indies Regiment stationed at Taranto in Italy.

More than 360,000 African-American troops, including over 600 officers, also served during the First World War, all of them in segregated units. Many did not serve overseas, and of those who did, the majority were used for non-combat duties. However, some regiments did fight alongside French troops and were famous for their bravery. Over 170 African-American soldiers were awarded the Légion d’honneur, the highest military decoration in France.

African-American troops also had to overcome the racism that was prevalent in the US army. One African-American soldier who died fighting in France was not awarded a medal by the US government until 1990. The participation of these troops in the war encouraged and inspired them to make greater demands for equality and an end to segregation and other discrimination when they returned home.

However, on their return, conditions were as bad as ever. Many African-American ex-servicemen faced racist abuse and attack, and in 1919, ‘race riots’ broke out in 25 US cities. Black ex-servicemen demobbed in Britain also faced racial violence, and in the same year, riots and racist attacks that led to several deaths occurred in British towns and cities, including Cardiff, London and Liverpool.

The Second World War

The African diaspora also made a major contribution during World War II, many giving their lives or enduring long periods of incarceration as prisoners of war. For example, thousands of Black troops recruited into the French army, including hundreds from the Caribbean, were held by the Nazis as prisoners of war or simply executed.

From the British West Indies, over 8,000 men and women were recruited into the armed forces and to work in essential war industries, although the army did not create a specific Caribbean Regiment until 1944. Several hundred men were recruited from the Caribbean to work in the armaments factories throughout Britain and as foresters in Scotland, while women were recruited into the Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS). Britain’s Caribbean colonies also contributed food, raw materials and money to the Allied war effort.

In Britain, too, many people of African origin joined the forces, became air raid patrol wardens or made other contributions. Over 200 people originally from the Caribbean lost their lives in Britain during the war and hundreds more were wounded. Once again, they all had to overcome the colour bar. The British government and armed forces were reluctant to recruit Black troops, and regulations were still in place at the start of the war to prevent the promotion of Black officers. Even on the home front, there were many examples of discrimination, the most infamous case being that of Amelia King, who was born in London but in 1943 was denied entry to the Women’s Land Army because she was Black.

African-American troops again served in the armed forces in large numbers – an estimated total of over one million men and women – approximately half of them overseas, but, again, in segregated regiments. Racism within the military meant that most troops were not directly engaged in combat and still faced discriminatory treatment and conditions of service both overseas and in the US. Despite this, some were decorated for bravery including Doris Miller, a cook in the US Navy who received the Navy Cross for his heroic action during the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941.

The ‘brain drain’

In Britain, the population of people of African origin increased substantially after the Second World War. Thousands of migrants came to escape the problems created by colonialism, first, from the Caribbean in the 1940s and 1950s (see The Windrush generation and then from various parts of Africa, especially former British colonies such as Ghana and Nigeria. The African and Caribbean communities have also had a significant impact on British culture. Today the country’s largest cultural event is the annual Notting Hill Carnival in London, a festival of Trinidadian origin that was first held in 1959.

The African diaspora has contributed in important ways to the economic development of many countries, as well as to social, cultural and political innovations of global significance. In Europe and North America, it is now common to speak of a ‘brain drain’ of well-educated people from Africa, the Caribbean and elsewhere, which has led to further changes in the composition of the diaspora in the years following World War II.

In Britain in 2005, for example, it was reported that over 12,000 doctors and 16,000 nurses had been recruited to the National Health Service from African countries, while a World Bank report estimated that there are over 70,000 African migrants to Europe and North America every year. Similarly large emigration takes place from the Caribbean to industrialised countries.

The fact remains that, more than two centuries after the British Parliament passed a law abolishing the transatlantic slave trade and over half a century since colonial rule was formally ended in many African and Caribbean countries, people of African descent are still being compelled to labour in and for countries that are far from their places of birth. The ‘brain drain’ is not just of direct economic benefit to the receiving countries. It is also a form of exploitation of those countries that have trained their citizens only to lose them overseas.

In recent years, the African Union (AU) – the African intergovernmental organisation– has officially recognised the African diaspora as a component of the African continent and has encouraged all those of African descent to contribute to Africa’s development. The AU has defined the diaspora as ‘consisting of people of African origin living outside the continent, irrespective of their citizenship and nationality and who are willing to contribute to the development of the continent and the building of the African Union’.

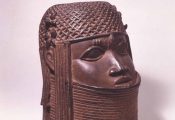

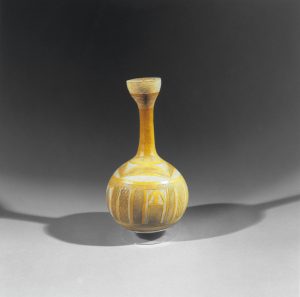

You can find artefacts in the theme of Diaspora.